As CEO of EmployAbility, Tab Ahmad helps bring down barriers to employment for graduates with neurodiversities, mental health issues and disabilities. But for years she coped alone with disabling panic attacks

When Tab Ahmad founded EmployAbility in 2006, she had a strong track record in finance and recruitment and considerable expertise in opening up employment possibilities for disabled and neurodiverse students and graduates. But she also brought to her new role decades of personal experience of panic attacks.

During the most acute periods, she has experienced three or four panic attacks a day. During an attack, she feels a sense of ‘impending doom’, as though she could die at any minute. There were a few months in 2001 which were, she says, ‘horrific’. She recalls flying back from her honeymoon with her husband and being convinced every moment she was in the air that the plane was going to crash. The worst attacks were at night. She went to work on two hours’ sleep. ‘If you have this, you learn very good coping strategies. For years I would just manage it – nobody knew, not even my team.

‘It’s only in the last five years that I have thought, “wait a minute – I actually have a disability”. I had imposter syndrome about having a disability – I thought I was a fraud, a cheat.’ She never spoke about her personal experiences publicly. ‘Until recently, I had a sense that this had nothing to do with my expertise. I felt it would be a cheap sell. I don’t feel that anymore, because there’s huge relevance.’

Before EmployAbility, Tab worked as a recruitment consultant in London, New York and Paris. She set up a head hunting firm, Rizwan Nash, which she ran for six years, specialising in finding equity analysts and fixed income quantitative analysts for banks and asset managers.

Her next move was establishing the graduate arm of a charity that supported disabled people into employment. ‘When I joined it was very white and male heavy. I was not taken seriously – to the point where people would say, “you don’t look old enough to know all that”.’

She struck out on her own, with EmployAbility, so she could ‘carry on making a difference’ in an organisation where she would have more control. But she says what drove her, above all, was the desire to awaken the business world to the potential of people with neurodiversities, mental health issues, and other disabilities.

‘There was a huge amount of talent being wasted. Companies were missing out too – they wanted the best talent out there, but they weren’t getting it. I wanted to support both sides. The idea was to empower the students to get the careers they deserved and support employers to be able to employ those people.’

‘At the time, disability was not one of the diversity strands that was on anybody’s radar. And even in the disability world, there was a feeling that if you didn’t have a physical disability, it wasn’t real.’

If mental health conditions and neurodiversities such as dyslexia, autism and dyspraxia had a low profile in the mid-2000s, they were practically invisible in the 1970s, when Tab was growing up. Looking back on her childhood, Tab can see that more than one member of her own family was affected by autism or OCD, but it wasn’t recognised at the time.

When she was in her early teens and living in Benghazi, Libya, with her biologist father, he woke her one night to tell her that their apartment building was on fire. ‘I jumped out of bed in my nightdress. Clutching his briefcase, he said, “It’s fine – I’ve got my PhD and our passports.”

They got out of the building unharmed and, at the time, she saw nothing unusual in his calmness. Indeed, it was ordinary, for him. ‘This I think was one of numerous examples of my father being on the autistic spectrum. He was never diagnosed, and it only occurred to me after he died.’

Around the same time as Tab and her father were escaping the fire in Libya, her older sister, a medical student in Iran, was hospitalised with schizophrenia.

The family reunited with Tab’s mother in London, the city where Tab was born, in 1964, to Indian parents who had recently arrived from Malaysia. She found her sister, who had been more like a mother to her than a sibling, ‘unrecognisable’. ‘I had lost the person I knew. It was a shocking summer.’ Her sister recovered and went on to marry and have a son, but within two years she had separated from her husband and was living with her parents. ‘She had a relapse and never recovered. My mother brought up my nephew.’

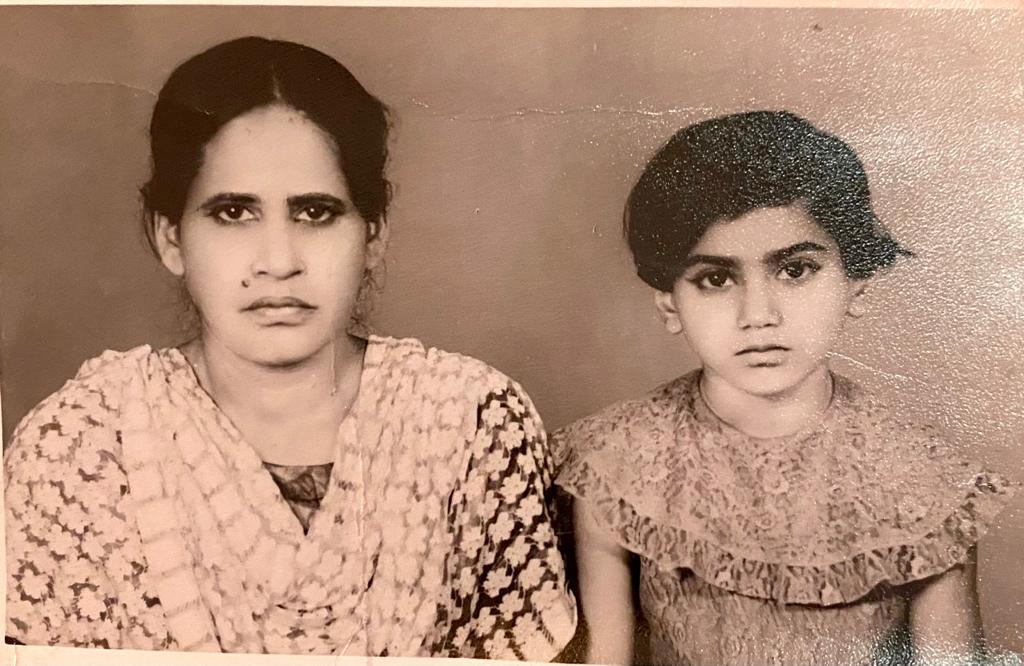

Her sister’s illness was the third great loss in Tab’s early life. The first was when she was 18 months old. ‘My father took the decision to send me to India to be brought up by his family there. That was traumatic for my mother and, I assume, for me. I was brought up by my paternal aunt until the age of five. I had a lot of love when I was there – I was quite spoiled – but then my mother brought me back to England. So that was another separation, from my aunt, my then primary caregiver.’

Asrauli, district Allahabad, UP, India.

Until she went to university to study Economics and Accounting, Tab never spent more than two years in the same school. Every time she was settled and making friends, a change in family circumstances – often her father gaining an academic post in another country – would mean she was uprooted and would have to start over again. There were positives in all the upheaval – she looks back fondly on her time with her father in the ‘beautiful, cultured’ city of Shiraz in south-central Iran – but there was no consistent parent figure and she struggled with forming lasting connections with people her own age: ‘It was quite disjointed.’

She had her first panic attacks between the ages of ten and twelve. They started after a minor accident when she got some broken glass in her hand. Her father, gently and expertly, removed the glass. ‘But because he was a biologist, he explained in great detail what could happen to me if the glass got into my bloodstream. It sent my imagination all over the shop. For several weeks afterwards, I wouldn’t eat anything that directly touched that hand, in case it had glass in it.’

In her current role, Tab sometimes encounters students and graduates who are also living with panic attacks. ‘I’m able to give them tips about things that have worked for me, because I’ve been through it.’ But she never presumes that her experience will be the same as anyone else’s.

Her panic attacks have never made her doubt her professional competence or made her feel that she can’t be successful, but she says the students and graduates she works with often lack confidence. ‘They might be at a good university, Oxford or Bristol, but because they have a disability they don’t feel good enough. I don’t identify with that because it’s not something I’ve experienced. But, I do have empathy. Everyone’s experience is different.’

EmployAbility provides one-to-one, individualised support to students and graduates, and increasingly to people at all career stages. ‘The difference between what we do, compared to other companies, is the level of detail,’ says Tab.

An individual’s particular neurodiversity, mental health condition, or disability – the ‘label’ attached to them – is less important, she adds, than solutions to the barriers that stand in their way. ‘For me, it’s about identifying and removing these.’ This involves educating the student or graduate, as well as the employer. Crucially, it means looking beyond legal rights and compliance to a more holistic, ambitious model of best practice – an approach EmployAbility calls Next Generation Inclusive Thinking.

‘We empower students, so they don’t see it as being given preferential treatment. It’s about levelling the playing field – because it isn’t level without adjustments. They don’t need to apologise. The flip side is how we convey that to employers. We advocate in the right way, and employers listen to us.’

With her team, Tab helps employers to ‘see the talent’. ‘It’s not about giving someone a chance because they have been through something, but it is about ensuring that everyone is given the opportunity to show their talent, irrespective of difference’.

With clients such as JP Morgan now speaking out publicly in support of EmployAbility’s ‘Next Generation’ approach to inclusion, the employment prospects for people with neurodiversities and mental health conditions are improving.

Tab was concerned that the coronavirus pandemic might stall progress but that doesn’t seem to be happening. ‘We are being contacted by huge numbers of companies who are thinking about inclusion. If nothing else, the pandemic has shown that it is possible to do things [in the workplace] differently. I’m really hopeful for EmployAbility and what we can achieve despite, or even because of, this pandemic.’’

Similarly, she says the Black Lives Matter movement – which EmployAbility fully supports – appears to be having a positive effect on disability awareness: ‘Employers are thinking more about how difference can be valued and supported.’

The past few months have been the busiest in EmployAbility’s history. Like every CEO in the country, Tab has faced the pressure of adapting to lockdown restrictions. But she hasn’t had to do it while exhausted from panic attacks. They’ll always feature in her life, but the severity and frequency has reduced, ‘If it was a 10 before, now it’s a 4. I know my triggers – I’m better able to look after myself now.’

She has also come to terms with the upheaval and losses she experienced in her childhood. ‘I’ve done a lot of work on myself. I’ve gone back and felt the emotions that would be appropriate, and come out the other side. And, of that, I’m proud.’